Wolves in sheep's clothing — Episode 1

CC # 138 — in which we provide our readers with some forgotten standards to evaluate the livability of new (and existing) homes and apply them to current and future "affordable" projects.

The past two generations has seen the elimination of most standards of home design. History provides a place to start analysis, critique and suggestions for a better future.1

“If you can design a good home, you can design anything,” said the late Norbert Schoenauer, one of my design professors at McGill University. Under his direction as Director of the School of Architecture as well as Design Professor, we learned how to design to at least the minimum Canadian standards of the day, as well as how to improve on them to optimize our designs.

As described in CC # 137, those minimum standards have been set aside for many so-called “affordable” housing projects in my hometown and many others. I have had many discussions with city hall planners, which summarize as “There are no standards for us to rely on anymore, making it very difficult to evaluate most proposals.” Yet schemes without room dimensions, without furnishings are planned, approved, built and marketed. This is unfair to all.

I have no influence over city halls. But I can perhaps better equip readers to evaluate the various schemes they are exposed to. I will do this by first providing a means to evaluate proposals, then applying it to a current so-called affordable rental project in my home city of Vancouver.

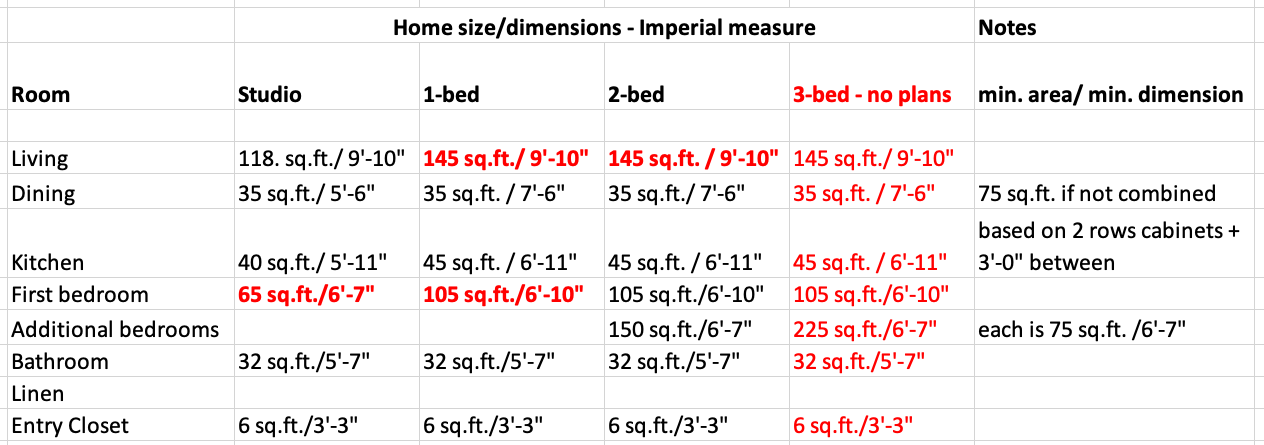

Firstly, my summary chart from CMHC’s Residential Standards, which were the country’s minimum standards until the 1980s—last time I checked, folks have not shrunk so these should still apply. Apologies for yet another such chart, but it’s what I do:

My summary—minimum room sizes and areas in a time when folks actually measured. Read on to find what the red means. Feel free to copy for your own use.

And again in imperial measure, to assist Vancouver’s Americanized planning department:

Each of the rooms in the left column used to be required in CMHC-financed homes. That’s important because in at least one of the current units I’ve evaluated, one of these basic rooms is missing. It’s been missing in action (MIA) for some years on many projects, yet last time I checked people still needed all these spaces.

The subsequent four chart columns above are CMHC’s minimum metric, then imperial areas and dimensional standards for each of these rooms in various sized homes—spoiler alert, several are allowed to be somewhat smaller in studios than larger homes. The cells in red type represent things that did not measure up in the sample I reviewed.

There’s been a lot of press lately (started by me but carried on by many others) about an almost completed project in Kitsilano with the exciting name of L2 (you can’t make this stuff up). L2 is touted as the answer to affordability. Enough said.

To be generous to L2, I looked at the largest floor plans on their website in each of studio, one and two bedroom homes. I could not find any three-beds although I was assured they exist—hence they are in red on my chart. Apologies for L2’s fuzzy graphics—they’re the best I could find on their rental site.

Here’s what I found:

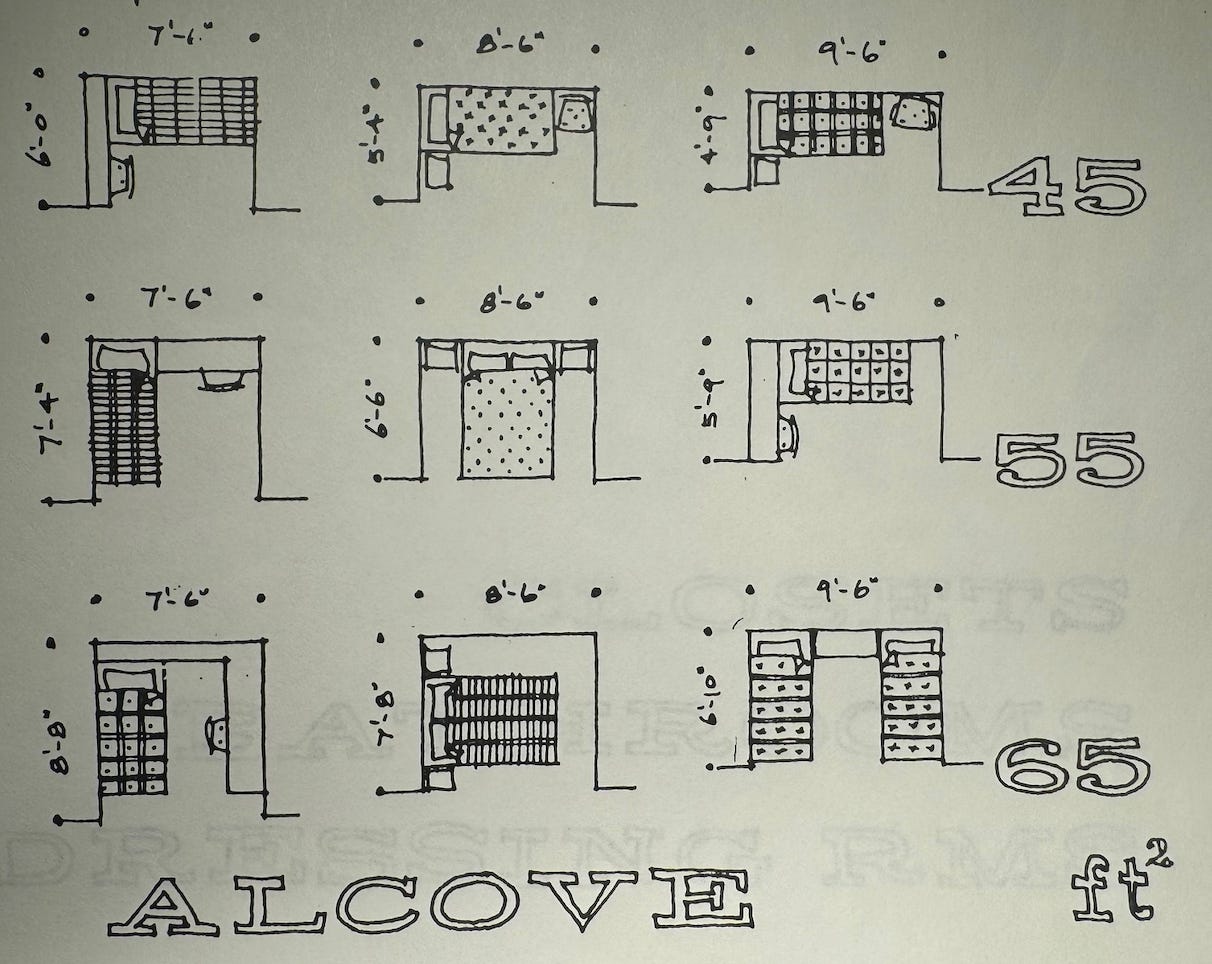

We’ll start with the largest Studio. What there is meets the minimum standards (barely in some cases) in my chart. But there’s nowhere for a bed! You can eat or you can sleep. I suppose there’s a Murphy bed option, but the minimum residential standards thought you were entitled to a dedicated sleeping alcove, as a minimum. Here’s what Norbert would have expected as a sleeping area in a studio:

Alcove sleeping areas for studios — minimum is at the top. Schoenauer then shows what happens when you add more space.

Back to L2 and its one-bed home:

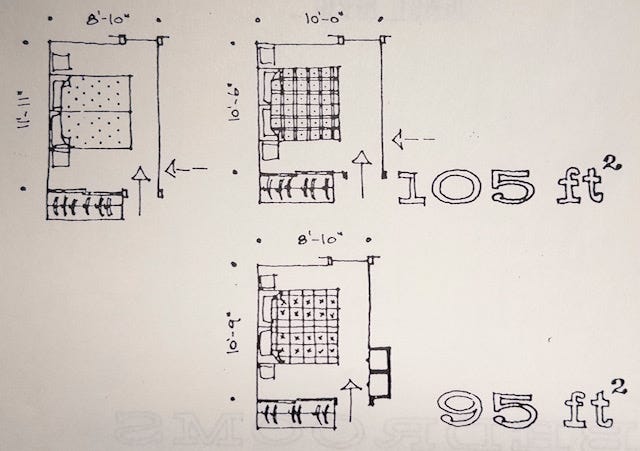

The largest L2 one-bedroom home is even more problematic. The living room is too narrow by two feet, the bedroom is too narrow, with barely enough room to squeeze by the end of a bed. Norbert would have been looking for something like what’s below to avoid issuing a failing grade for the master bedroom:

Minimum master bedroom space at the bottom, then with 10 square feet added.

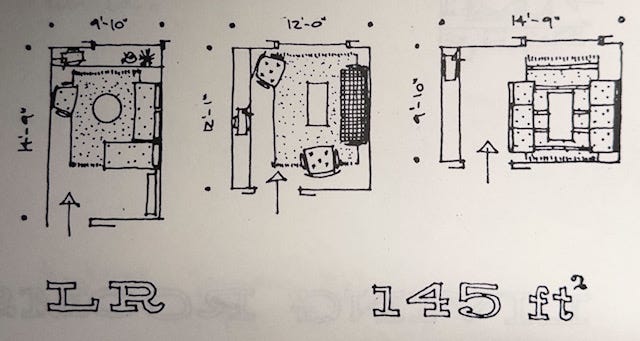

L2’s largest two-bedroom home has a living room too narrow by more than two feet. Again, here’s what Norbert would have looked for in the living room:

Minimum living room spaces as sketched by Norbert Schoenauer

What does all this mean for you readers?

If L2’s cousin comes to your neighbourhood, ask (ideally) at the public information stage why the homes are not shown furnished. Better designers should have a CAD (Computer Aided Design) layer showing furnishing, which can be turned on to show you whether a space is livable. There is no excuse.

If a basic element is missing, like a place for a bed or to eat, ask where it is. A home without both a bed and eating space is a Single Room Occupancy (SRO) regardless what fancy name it’s labeled. Folks on more limited incomes also need to eat and sleep.

Even if you’re not moving in, think about how upset and grumpy your future neighbours will be if they have to choose between eating and sleeping.

So the next time you are evaluating a project at the planning stage, or a home in it, ask to see the plan furnished. If the designer can’t make it work on paper, you’ll not be able to make it work as a home.

DISCLAIMER: As a registered Architect, I am unable to be too critical of my peers lest I be accused of unprofessional conduct. However, I believe I am permitted to compare the work of others to reasonable design standards. Hopefully they will agree.

The post above is 939 words, takes me 5 minutes to read—2 minutes more than what citizens are now allowed for presentations to Vancouver City Council.

If you appreciated this post, please share to your social media and consider becoming a free subscriber to City Conversations at

Brian Palmquist writes on the traditional, ancestral and unceded lands of the Musqueam people. He is a Vancouver-based architect, building envelope and building code consultant and LEED Accredited Professional (the first green building system). He is semi-retired, still teaching, writing and consulting a bit, but not beholden to any client or city hall. These conversations mix real discussion with research and observations based on a 50-year career including the planning, design and construction of almost every type and scale of project. He is the author of the Amazon best seller and AIBC Construction Administration course text, “An Architect’s Guide to Construction.” A glutton for punishment, he recently started writing a book about how we can Embrace, Enhance and Evolve the places we love to live.

from Schoenauer, Norbert, Towards Optimum Standards, a 1967 unpublished monograph that I was able to get a photocopy of in the early 1970s.

What are the long term social and health effects of cubby-hole apartments and condos?

What are the social costs of mini sized accommodations?

How does simply warehousing people in substandard high rise hovels affect the social fabric?

I do not think our locals know and our politicians do not want to know.

I have seen it and it was called the 'Roundshaw' estates in South London, when I lived in Wallington in 1980.

It was evil and was a breeding ground for social decay, corruption, and dystopia. The quaint English "No-Go" areas was coined for Roundshaw and the many other housing estates like Roundshaw that dotted London.

Today, the towers are gone and in their place scalable, two to three story maisonettes, which have replaced a dystopian landscape to at least a livable one.

But of course, Eby's housing policy is ll about land speculator/developer profit and to hell with the poor souls who are destined to live in Vancouver's version of Roundshaw.