Wolves in sheep's clothing — Introduction

CC# 137 - in which we lay out our bases for evaluating the blizzard of housing announcements arising from the upcoming government elections and ongoing "initiatives"

The cover of probably the last Canadian planning document that underlay the last generations of truly affordable, livable homes. Notice they’re all working together.

The post below is 750 words, takes 4 minutes to read—one minute more than citizens are now allowed for presentations at Vancouver Council meetings.

“What happened to the homes, the yards, windows, rooms you could furnish, the privacy—all those things we grew up with?” My 30-something son was complaining about the redevelopment threats to his older studio walkup apartment in Vancouver, too close to SkyTrain to escape developer notice. When he is demovicted, the replacement studio will be 100 square feet or more smaller than his 450 square foot space, which I would describe as “cozy” rather than spacious.

I have to start by admitting that we are both privileged. He and I before him grew up in homes with those elements, which every day seem to be resized or removed altogether. Most folks don’t know how we have come to this pass—I’m old enough that I have some thoughts and knowledge.

The first decade of my architectural career was largely spent designing social housing around the Lower Mainland of BC—everything from subsidized rental homes on free or cheap land, through co-operative housing and even including affordable (yes!) strata housing. Our planning bible was Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC’s) Site Planning Criteria1, last published in 1982.

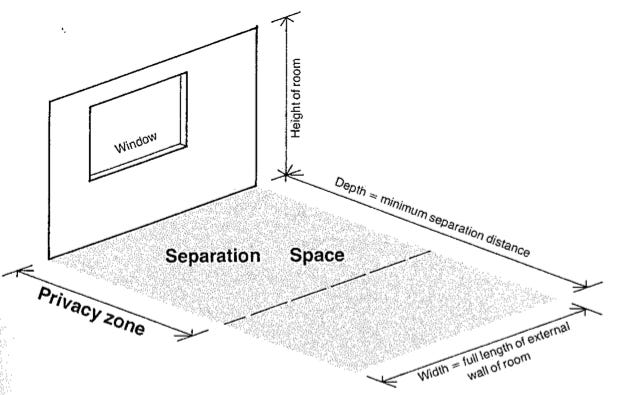

The Criteria was dear to the hearts of planners and designers alike, public and private sector. It established minimum standards for things like the separation spaces between homes and between various types of rooms in a home and adjacent homes:

A synopsis of concepts in CMHC’s 1982 Site Planning Criteria, page 33

Many of the yards, walkways and other separation spaces that you grew up with came from the Criteria. CMHC funded so many affordable projects in those days that architects and designers ignored them at their peril. I certainly didn’t.

The companion volume to the Handbook was CMHC’s Residential Standards, last published in 1980. It had the temerity to include a Section 5—Room and Space Dimensions, which established just that—minimum floor areas and dimensions for living, dining, kitchens and bedroom areas, even including closets, hallways and services spaces. Again, many of us have grown up in or moved into older homes designed to these standards.

The introduction to the four pages out of 3002 that described minimum residential space sizes in 1980.

Those two publications were all that Canadian planners, designers and architects needed to plan livable, affordable homes until they ceased publication two generations ago. In the succeeding 40+ years most of these planning and design standards have been set aside—I believe the excuse is that CMHC’s involvement in residential development has diminished. Yet despite everything becoming smaller and denser, it’s all way more expensive.

Patrick Condon’s book Broken City3 is one of several credible explanation of much of what’s gone wrong on the land price side. I highly recommend it. If you’d told me in 1980 that the 15 square meter shaded separation space in the Handbook diagram above was today worth $50,000-75,0004 and up—just the dirt—I’d have laughed in your face. Apologies.

I believe it’s the abandonment of planning and design standards grounded in psychological, behavioural and social sciences5 that has caused many of today’s affordability issues. Simplistically, if there’s nobody telling a planner, designer or builder otherwise, what will prevent them from doing away with things like: dining spaces; bedrooms that can be furnished; outdoor spaces? What will prevent the authorities from acquiescing to continued pressure to build simultaneously smaller, denser and higher? While proponents pocket the profits, society as a whole deals with the fallout—families that have little or no space large enough to even gather, let alone spread out to do homework, pursue a hobby, just sit and read. And these are just the gentle outcomes.

There are certainly other aspects of our society that contribute to the challenges we face. I am not competent to speak to them. But with shelter being one of only two prerequisites for survival (the other being food), I hope there is some value in my observations.

I am calling these next episodic posts Wolves in sheep’s clothing because in my opinion they represent bad things being done under cover of good words. The good words include affordability, social housing, etc. Others may emerge as we explore.

The bad things under the sheep’s clothing include the antitheses of the good words: “poor doors6” to separate those in social housing from others in a building; loss of sunlight, privacy, view; rents that are “affordable” except they’re not to most folks; questionable public loans to private interests; etc.

Strap yourselves in! I will try to address some situations before the upcoming provincial election, perhaps to help you decide who to vote for. Thanks for reading.

If you appreciated this post, please share to your social media and consider becoming a free subscriber to City Conversations at

Brian Palmquist is a Vancouver-based architect, building envelope and building code consultant and LEED Accredited Professional (the first green building system). He is semi-retired, still teaching, writing and consulting a bit, but not beholden to any client or city hall. These conversations mix real discussion with research and observations based on a 50-year career including the planning, design and construction of almost every type and scale of project. He is the author of the Amazon best seller and AIBC Construction Administration course text, “An Architect’s Guide to Construction.” A glutton for punishment, he recently started a book about how we can Embrace, Enhance and Evolve the places we love to live.

The Vancouver Public Library has a single paper copy of the Criteria, which CMHC stopped publishing as it got out of the affordable housing business. Like most CMHC publications, it has no attribution to authors.

The remaining 296 pages of Residential Standards comprised minimum construction standards for single family homes.

Condon, Patrick, Broken City - Land speculation, Inequality and Urban Crisis, Vancouver, B.C., UBCPress, 2024.

Lots in Vancouver are worth $1 million, $2 million and more. Simple math makes that $300 to $500 or more per square foot of dirt. Simple math accounts for the rest.

I’ll bring the sciences into the mix when I get into the details in future episodes.

Poor doors really exist and are an increasing cancer in cities as disparate as Vancouver and New York City. They occur where folks living in any kind of subsidized homes have completely separate entries and circulation from those fortunate enough to be able to afford market rents or purchase prices. City planning staffs do not prohibit them. I’m mortified that some architects agree to design them

Thank goodness for your dedication to speaking out on issues that many fear to address without the protection of anonymity. Vancouver is spiraling into chaos, with skyrocketing rents and housing costs making it nearly impossible for most residents to get by without working two or more jobs. Many Vancouverites are too busy struggling to make ends meet to truly grasp the scope of what's happening, and it’s crucial that they understand that their knowledge AND voices, matter!

I strongly believe that a thorough investigation into the inadequacies of the BC Societies Act is long overdue. This outdated legislation is contributing to an increasingly dystopian housing landscape, where non-profit housing providers and developers are capitalizing on loopholes and exploiting what should be affordable housing. These organizations are profiting under the guise of social good, all while there is little to no accountability or enforcement to ensure these homes remain truly affordable and livable for Vancouver residents.

The lack of proper oversight under the BC Societies Act allows these housing providers to operate without sufficient checks and balances. This problem, coupled with the ongoing housing crisis, has created a perfect storm. There needs to be more transparency, stricter regulation, and better enforcement to ensure that affordable housing projects are genuinely benefiting the people they’re supposed to serve. Currently, this essential accountability is missing.

Interesting premise for an excellent series to come. Looking forward to it!